The femoral neck-shaft angle (NSA) or caput-collum-diaphyseal (CCD) angle is one of the most frequently applied measurements to assess hip morphology, in particular, the relation of the femoral shaft to the femoral head-neck axis.

Coxa valga is defined as the femoral neck shaft angle being greater than 139 ° [1]

Coxa vara is as a varus deformity of the femoral neck. It is defined as the angle between the neck and shaft of the femur being less than 110 – 120 ° (which is normally between 135 ° - 145 °) in children. [2]

Coxa vara is classified into several subtypes:

- Congenital coxa vara, which is present at birth and is caused by an embryonic limb bud abnormality.

- Developmental coxa vara occurs as an isolated deformity of the proximal femur. It tends to go unnoticed until walking age is reached, when the deformity results in a leg length difference or abnormal gait pattern.

- Acquired coxa vara is caused by an underlying condition such as fibrous dysplasia, rickets, or traumatic proximal femoral epiphyseal plate closure. [3]

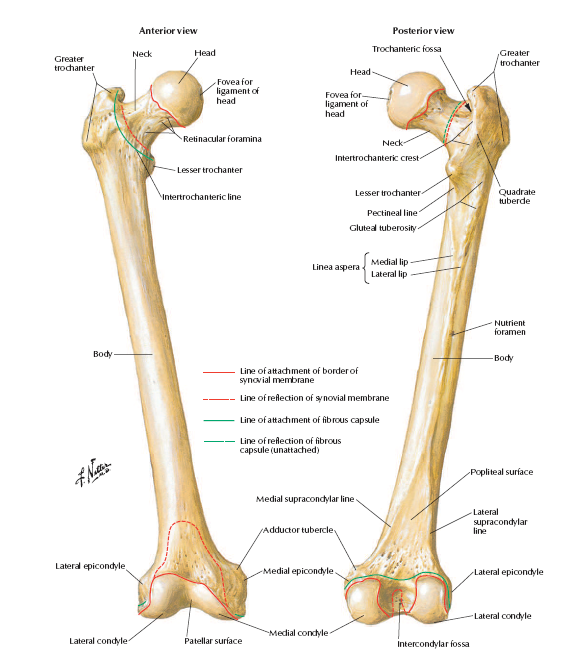

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

Congenital coxa vara results in a decrease in metaphyseal bone as a result of abnormal maturation and ossification of proximal femoral chondrocyte. As a result of congenital coxa vara, the inferior medial area of the femoral neck may be fragmented. A progressive varus deformity might also occur in congenital coxa vara as well as excessive growth of the trochanter and shortening of the femoral neck. [4]

A review on the development of coxa vara by Currarino et al showed an association with spondylometaphyseal dysplasia, demonstrating that stimulated corner fractures were present in most instances. [5]

Ashish Ranade et al also showed that a varus position of the neck is believed to prevent hip subluxation associated with femoral lengthening. An associated dysplastic acetabulum can lead to a hip subluxation. In this case study, the acetabulum is abnormal in coxa vara. Acetabular index (AI) and sourcil slope (SS) are significantly different than in the normal acetabulum. [6]

Epidemiology /Etiology

Femoral neck fractures, less than 1 % of all pediatric fractures in children, are associated with a high incidence of complications. The most serious ones with high and long term morbidity being osteonecrosis and coxa vara. [7]

A retrospective study of femoral neck fractures in children show the following complications: [8]

1) avascular necrosis (14.5%)

2) limb shortening in seven (11.3%)

3) coxa vara (8%) and premature epiphysis fusion (8%)

4) coxa valga (3.2%), arthritic changes (3.2%).

5) non-union in one (1.6%)

Premature epiphyseal closure is described as one of the ethiological factors of coxa vara. Incidences of premature physeal closure reported in the literature range from 6 % to 62 %. Another possible explanation for the high occurrence of coxa vara is the loss of reduction after initial fracture reduction of implant failure in unstable fractures. Developmental coxa vara is a rare condition with an incidence of 1 in 25 000 live births. [9] Incidence of coxa vara can be decreased by using internal fixation such as pins or screws. [7]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

Clinically, the condition presents itself as an abnormal, but painless gait pattern. A Trendelenburg limp is sometimes associated with unilateral coxa vara and a waddling gait is often seen when bilateral coxa vara is present. Patients with coxa vara often show:

- Limb length discrepancy

- Prominent greater trochanter

- Limitation of abduction and internal rotation of the hip.

Patients may also show femoral retroversion or decreased anteversion.[10]

Diagnostic Procedures

Radiography (AP view of the pelvis) can be utilised to determine the HEA (Hilgenreiner Epiphyseal Angle). Signs to look out for are as follows:

- The neck; shaft angle is less than 110 – 120°.

- The greater trochanter may be elevated above the femoral head.

- A growth plate with an overly vertical orientation. [11]

MRI can be used to visualise the epiphyseal plate, which may be widened in coxa vara.

CT can be used to determine the degree of femoral anteversion or retroversion. [12]

Examination

AP radiographs in standing are taken, usually of both hips in a neutral position. Measuremenst are then taken: the Acetabular Index and the Sourcil Slope (the angle formed by a line joining the 2 ends of the sourcil with the horizontal line) [6]. Subluxation in children is measured by the Migration Index and the Centre edge Angle.

Medical Management

The objective of medical interventions is to restore the neck-shaft angle and realigning the epiphysial plate to decrease shear forces and promote ossification of the femoral neck defect. This is achieved by performing a valgus osteotomy, with the valgus position of the femoral neck improving the action of the gluteus muscles, normalising the femoral neck angle, increasing total limb length and improving the joint congruence.

The following are indications for surgical intervention:

- Neck: shaft angle less than 90 °.

- Progressive development of deformity.

- Vertical physis and a significant limb.

Other indications are based on the HE angle;

- HE angle > 60 ° is an indication for surgery.

- HE angle 45 – 60 ° warrants close follow up.

- HE angle < 45 ° warrants spontaneous resolution

Except when the neck/shaft angle is less than 110°, progression of the varus angulation takes place, gait pattern abnormalties or degenerative changes take place. [13]

Physical Therapy Management

Literature is lacking, but surgical management appears to be the accepted treatment protocol for this condition.

Clinical Bottom Line

Due to the low incidence of coxa vara and even lower for coxa valga, there is little literature currently available. There are 3 types Coxa Vara, acquired, congenital and developmental, usually displaying greater acetabular dysplasia and an abnormal acetabulum. Surgery is the most effective treatment protocol. In the case of acquired coxa vara from a fracture, the proximal femur and femoral neck need accurate reduction and rigid fixation to avoid potential serious complications.