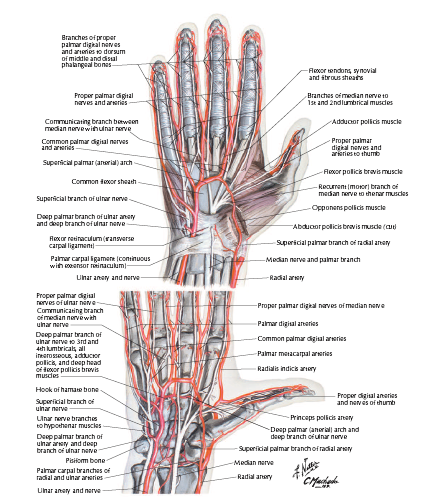

The blood supply to the hand is predominantly built-up of anastomosing vascular networks known as the superficial palmar arch (SPA) and the deep palmar arch (DPA), with the DPA found proximal to the SPA.1 The SPA is commonly formed by collateral circulation between the ulnar artery (UA) and the superficial branch of the radial artery (RA), with the UA dominating this blood supply.2 The RA then continues to anastomose with the deep branch of the UA resulting in the DPA, with the RA dominating this supply.2 Nonetheless, both arches demonstrate a high prevalence of anatomical variation which stems from embryologic development.3, 4 Arey5 suggests that deviation from normal vessel development in the hand may be due to the persistence of vessels which normally regress during the embryogenesis. The median artery (MA) predominates as the axis artery of the upper limb and degenerates when the UA and RA are ready to supply the blood to the hand,6 but it might persist and consequently contribute to the vascular supply of the hand.

An in-depth knowledge of anatomical variations of the palmar arches (PAs) is essential for improving surgical techniques and identifying the pathophysiology underlying diseases of the hand.8 One of such deviations, leading to clinical complications can be a persistent MA, shown to increase surgical accidents, i.e., hand ischemia or carpal tunnel syndrome, in what would otherwise be a routine surgical procedure of the hand or the wrist.9 The presence of this artery, not regressed during the fetal life, can lead to unprecedented and excessive bleeding during wrist surgery and can potentially cause carpal tunnel syndrome once an aneurysm, thrombus, or compression of the median nerve by the MA occurs.